|

John Hennessey: The Budd family & The Island ... scroll down for some great pictures of the island.

|

|

|

You can also read about my visit to the Eastern Cape in South Africa to view Dr Budd's grave. The early 1900s and the Great War The beginning of the 20th Century sees Herbert Hayward Budd, a 15 year old boy, living with his father, Herbert Goldingham, at College Gates, 106 High Street Worcester. Herbert Hayward’s father, then 57 and approaching the end of his life, was a prominent member of the Worcester professional classes – honorary surgeon to the Worcester Infirmary, surgeon to the Worcester Ophthalmic Hospital and Surgeon Lieutenant Colonel to the 5th Battalion the Worcester Regiment. Unfortunately ill-health was to dominate the early part of the first decade for this family. On 23rd July 1900 Herbert Goldingham altered his earlier will (of 1886) anticipating the events which were to follow. We cannot tell the health of his much loved wife Harriet (whom he fondly calls ‘Minnie’) in 1900, but Herbert changed the terms of his will (which had previously left all his possessions and personal estate to his wife) to appoint his friend Joseph Parry Laws, a local chemist, to be Guardian of his son Herbert Hayward upon his death and also to be Trustee and Executor of his will. Instead of bequeathing the original sum of £100 to Harriet, he reduced this sum to £50, bequeathed her for life “plate, linen, china, books, pictures, wines, furniture, personal ornaments, and other household effects…and all my carriages, horses and harnesses and outdoor effects” but added the caveat: “But if at the date of my decease the sate of her health shall in my Trustees’ opinion preclude her from living at my house and enjoying the use of such furniture and such effects, then I direct my said Trustees to sell the same and to stand possessed of the proceeds thereof Upon Trust thereof to invest the same and pay the income thereof of my said wife for her life and after her decease Upon Trust to pay the proceeds of such sale and the income thereof equally between my children or child if only one.” On the evening of 31st March 1901, census night, we find Herbert Goldingham living at College Gates with his son and their 2 servants, but Harriet Amy at home with her parents (Robert and Henrietta Cole) in Dawlish, Cornwall. Whether she was ill at this time and was convalescing with her parents, we do not know. Less than 2 years later, her state of health becomes apparent on the death of her husband. Herbert Goldingham Budd died on 4th November 1902, aged 60. His sister, Emily, was with him when he died. His obituary in the British Medical Journal describes the manner of his death: “He was apparently in his usual health on the day of his death, but whilst stooping to put on his boots after breakfast he suddenly fell back and died in a few minutes. His health had not been good since a severe attack of pneumonia about two years ago.” It also recounts the high esteem in which he was held: “His fresh complexion, well-knit figure, and military carriage were well known in Worcester, where he was beloved by his patients and greatly respected by those who knew him.” In accordance with his will, as Harriet is ‘not competent’ at time of death, the house at College Gates is sold (£1050 gross), and the net proceeds of his estate £449 5s 11d are invested. We can only assume that the young Herbert Hayward (then 17 years of age) is looked after by Joseph Laws, or perhaps by his aunt Emily (his other Aunt Lucy by then being married and living in Stevenage with her own children). By the time of the 1911 census in April of that year, Harriet Budd is interred at Powick Worcester and City Lunatic Asylum, where she was to remain for the rest of her life – a period of over 30 years. On a more positive note, in April 1911 Herbert Hayward Budd, by now man of 28, is to be found in lodgings in Paddington, London, where he is a medical student at St Mary’s teaching hospital. In June of that year he qualified Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery of the Society of Apothecaries (LMSSA). Whilst not the medical degree his father gained, it nonetheless marks the beginning of his medical career and the entry of the third generation of Budds into the medical profession. His affectionate title ‘The Doc’ was to stay with him for the remainder of his life. Initially working in Kilburn, North London, Herbert found his way to Kinson in Bournemouth by 1915. Living at ‘Elm Brook’, we believe with his aunt Emily, he worked as a doctor during the early part of the Great War. During this time he became family doctor to the Sopers, then living at neighbouring Bare Cross. Head of the family was William (51 years old in 1915, a milkman), married to Louisa (46 years of age), with children William (23), Maud (19), Edith (18), Kate (14), Bertie (12) and Alfred (6). Their eldest daughter, Lisle Louise (22), always called ‘Lisle’, was a servant girl to a family living on private means in nearby Boscombe. Maud was servant girl to Herbert’s aunt at Elm Brook during this time. Family history relates Dr Budd treating Lisle for ‘consumption’ (Tuberculosis), which is perhaps how their paths crossed. Apparently remarking to William, Lisle’s father, that Lisle ‘was the sort of girl he’d like to marry’, they somehow became connected and the seeds of their romance and short life together were sewn during this time. With the Great War calling upon an ever increasing commitment across the British Empire, in common with so many others Herbert Budd joined the War effort and was enlisted as a Temporary Surgeon Lieutenant in the Royal Navy on 12th June 1915, initially posted to Haslar Naval Hospital in Portsmouth. At this point a theme emerges in Lieutenant Budd’s affairs, of which little can now be determined. The entry of 13th July 1915 in his service records reads: “informed will be kept at Haslar if poss[ible] during litigation.” By early November he was nonetheless posted – to 20 Royal Naval Air Squadron at Clement Talbot Works, Wormwood Scrubs in London. Here he was surgeon to a detachment of the experimental branch of the Air Squadron, where new vehicles and searchlights were being developed. At this point we understand that Lisle followed Herbert to London, and worked in a parachute factory (although no more details are known). January 1916 sees a reappearance of trouble for Herbert with a Debt Case entered against his name in the Admiralty index of papers (unfortunately no more information is available). Later that year his time ashore comes to an end when he is posted to HMS Armadale Castle. Built in 1903 for the Union Castle line (running shipping routes from England to South Africa), the Armadale Castle was converted to an armed merchant cruiser in August 1914 and was pressed into Navy service until the end of the War. At nearly 13,000 tons she could carry crew and passengers of over 1,000. During the War she was used as a supply, transport and patrol vessel. Travelling via Durban and Cape Town, Lieutenant Budd joined the Armadale Castle at Simonstown on 13th September where she had just left dry dock. Following a short period of taking on fuel and stores at Cape Town (including a secret consignment of gold bullion valued at £4m to help fund the war effort), the Armadale Castle sailed for Halifax Nova Scotia on 20th September 1916. At just after 8am that morning, Lieutenant Budd passed the small rocky garrison of Robben Island, a place he was to return to 4 years later. Whilst we cannot know the origins of his desire to later live and work in South Africa, it seems reasonable to assume that it can be traced to this early encounter with the region. By 3rd November the Armadale Castle arrived at Porto Grande, St Vincent (Grenadines), took on fuel, and then immediately set sail for Halifax, arriving on 10th October. By 1st November Armadale Castle was again at sea, carrying 4 officers and 123 ratings of the Canadian Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (destined to support Britain in her War effort), bound for Liverpool, her home port. Arriving on 11th November, having discharged her passengers and cargo, she began a 2 month period of refit, with at times more than 200 civilian workers aboard. Taking advantage of this time alongside, Lieutenant Budd took shore leave and traveled to London where Lisle was waiting for him. On 21st November, 1916, Herbert Hayward Budd (32), Surgeon Royal Navy, married Lisle Louise Soper (23) at Hammersmith Registry office (it’s likely that Lisle was living there, still working in the parachute factory). At Elm Brook, Kinson, it’s understood that Herbert’s aunt Emily immediately dismissed her servant girl, Maude (Lisle’s sister), as it was not appropriate to have a sister in law engaged as a servant. The Sopers and the Budds were joined by marriage but the class divide was never bridged; Lisle never mixed with nor spoke of the Budd family in later life. Nonetheless, Lisle’s life was to be fundamentally transformed by the marriage to Herbert – her servant days were over. January 1917 sees the Armadale Castle complete her refit at Liverpool and Lieutenant Budd rejoining ship. Following a short period of gun trials, the Armadale Castle made for the North Sea for the first of three patrols Herbert was to undertake that year. Patrolling the Nordic coastlines, Iceland and the far reaches of the North Sea, these month-long winter patrols would have been arduous and uncomfortable (reports of ice packs are found in the Ship’s log on one patrol, and there is regular damage to the vessel due to high seas and storms). Often boarding merchant vessels (and on at least one occasion transferring Lieutenant Budd to provide medical assistance), these patrols were designed to protect Britain’s northern maritime borders. In July 1917 we see more evidence of financial troubles for Herbert with a further Debt Case entered against his name in the Admiralty papers. At the end of July, perhaps missing his new wife too much, or needing to sort out his personal affairs, Lieutenant Budd applied for a shore appointment. The entry in his service record is terse, and can only reflect the manner of the reply he received: “on applic[ation] for shore appt, [Director of Surgeons] points out offr was on shore till aug 1916 + might have managed his personal affairs then. He does not think his pecuniary loss can be ascribed to the service”. It is perhaps all too tempting to be cynical about what happened next, but within three weeks of receiving this reply, Lieutenant Budd left the ship suffering from ‘poss[ible] motor attacks’ and was sent to Haslar Naval Hospital where he began his Navy career. There he is discharged ‘unfit for further service’ on 14th September 1917. His replacement on the Armadale Castle, Surgeon Mungo McKerrow, sees out the War serving on this ship. Not much is known of Lisle’s and Herbert’s time between 1917 and 1920. We do know they lived in Shrewton, Wiltshire, where the now civilian ‘Doc’ was the village doctor. Living in war-time Britain as a man appearing capable of serving his country was often uncomfortable. In order to explain the situation, wearing the Silver War Badge (or the ‘Silver Wound Badge’ as it was often known), denoting disability in service, was commonplace. Herbert applied for the Badge in April 1918 – his application was refused which perhaps says something of the manner of his departure from the Service (although he was subsequently awarded the Victory and British War medals at the end of the War). During this time we know that Lisle rented a house for her parents in Wallisdown, Bournemouth. Number 9 Priestly Road was secured for them and William and Louisa lived there until they died in the 1940s It was also to become Lisle’s home and remains in the family to this day.

The end of the Great War in November 1918 sees Herbert’s thoughts turning to more exotic places than rural Wiltshire where he then finds himself. In May 1919, in connection with his application for overseas service, the Colonial Office requests a report on his service from the Navy. The reply noted in his service record is less than flattering: “from personal observation he [Director of Surgeons] is doubtful of this officer's intellectual ability”. Despite this Dr Budd is appointed to the Mental Hospital Service in South Africa. The Doc and Lisle obtain their passport to travel in November 1919 and prepare to leave England for Robben Island. As they celebrated New Year 1920, The Doc’s and Lisle’s thoughts must have been full of hope anticipation at the adventure which lay ahead of them, not least because by this time Lisle was pregnant with their first child.

See John's own family tree here ... |

|

Pictures also survive of a holiday to the fashionable Clifton area on the mainland, along with social gatherings – whilst isolated, life appears to have been good, and most certainly very different for Lisle from life as a servant girl in Boscombe. Little of The Doc’s work is known. Whilst his appointment was to the Mental Hospital Service, the facilities on Robben Island catered for both mental patients and lepers at the time of his arrival. The high cost of providing treatment on the Island caused the mental patients to be transferred to Cape Town (to the Valkenburg Hospital, still in operation today), leaving only the lepers on the island by 1921. Nonetheless The Doc remained on the Island – we can therefore presume that he worked in the Leprosarium there. By 1927 we know that The Doc was spending time a long way from home in Umtata (some 700 miles away in the Eastern Cape). By this time he was Medical Superintendent of Robben Island. This year was to be filled with sadness for the Budds. In May of that year Herbert’s aunt Emily died in Stevenage, aged 86. Her bequest of £2,000 to her nephew Herbert perhaps underlines the relationship between them.

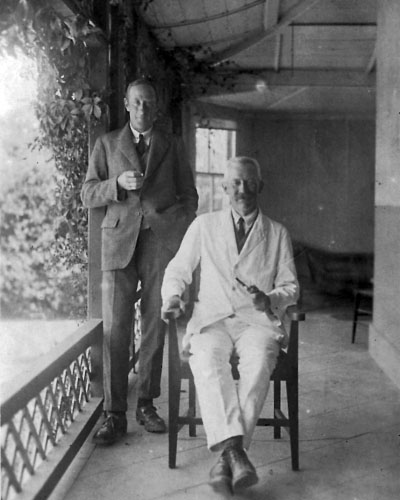

Robben Island and the inter-war years Not much is known of the time Lisle and the Doc (Herbert Hayward Budd) spent in South Africa. From existing documents we can however piece together something of what happened during this time. The first mention of The Doc is in March 1920 when his appointment to the Mental Hospital Service, serving on Robben Island, is recorded in the South African Medical Record. Lisle and The Doc set up house on the Island, a small, flat and rocky feature only 3.3km long by 1.9km wide (and 8km off the coast of Cape Town) which had variously served as a garrison, hospital and prison since the late 1400s. The community on the Island was small and electricity was only available from a portable generator which served the island cinema. A flock of 150 sheep grazed on the island in case the ferry could not get through from the mainland with food. Life was certainly isolated. Their first and only child, a son, William Hayward, always called Billy, was born on 11th September 1920, and baptised 2 months later. Billy’s Godfathers were Doctor Thomas Davies and Mr William B De Smidt. The Doc and Doctor Davies seem to have been good friends; photographs of them sharing a drink together during a shooting expedition and relaxing on Doctor Davies’ veranda survive. Despite the small size of the Island, the Budds had a car and the Doc built a boat - see below.

|

|

Leper Staff, 1927 with Dr Budd third from left, middle row.

Dr Budd (Left) with nurses in the Robben Island Infirmary. Likely to be for the treatment of lepers (mental patients were housed on the Island until 1921, after which they were moved to Valkenberg in Observatory, Cape Town, and only lepers remained on the island).

Group photograph taken in front of the Medical Superintendent’s house (where they lived from 1924). Lisle Budd far left, Billy Budd centre. Reverse of the photograph: “Buddy Mani? Biggs, Hore? Dunbar, Dorothy Billy. Robben Island +/- 1924”. The affectionate pose between Dorothy and Billy might indicate she was his nanny? Note the distinctive trellis-work around the door. This was the only house to have such a feature and clearly identifies it (by reference to other contemporary photographs) as the Medical Superintendent’s house. It was the second highest status house on the Island (after the Commissioner’s house) and overlooked the cricket pitch.

Billy on donkey, with his mother, Lisle, 1923/4.

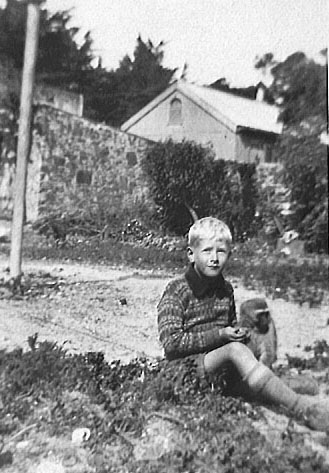

Billy Riding, 1925. Reverse of pic states: “For Mother. Billy 5 & half years. Billy and I”. Billy with Monkey, circa 1926.

Robben Island Mule Cart.

View of the cricket pitch looking towards the Medical Superintendent’s house.

Large group photograph of members of the Robben Island Staff, taken sometime after 1924.

From research at the National Library of South Africa, individuals can be identified as follows: Back row: Willie King (bakery), George Epre (stores), Mr Wusherpfennig (chief warder, convict station), Mr Coward (Lighter ?), Paddy Byrne (Chief Boatman), Larry S? (Boatman), W Cummerford (Baker), Teddie Bomdt (Butcher), Albert Johnston (Boatman). Centre: George Howell (Stores manager), Mr de Smidt (Head P.W.D.?) Dr Budd (Medical Officer), Mr J Alexander (Commissioner), Jeremy Miller (Chief Clerk), Cann Clemudson (Anglican Minister), Capt Schiel (Capt SS Pieter Faure). Front Row: RG Williams (Stores), Pierce Cummerford (Bakery), Geroge Haupt (Office messenger), W Gibbs (Clerk), Jock Miller (Clerk), Mr Page (Stores). |

|

|

On 14th September, 3 days after Billy’s seventh birthday, The Doc died suddenly following a brief case of pneumonia. Tragically for Lisle this happened while the Doc was away in Umtata. Due to the heat and poor communications it was not possible for the Doc’s body to be brought back to Robben Island and so he was buried in Umtata Cemetary. Neither Lisle nor Billy could attend the funeral. Oral history relates that Lisle was devastated by his death and vowed never to attend a funeral again and indeed she did not attend her parent’s or her sister Kate’s funerals years later. The Doc’s estate papers give a picture of his affairs – hotel and shop accounts to be settled in Umtata, a car recently bought there, a boat and a car by way of possessions on Robben Island. His comfort with debt was to take its toll, with over half of his estate being required to be paid out to settle debts (running to £399, [box back to his wages]). With the addition of his Aunt Emily’s bequest, Lisle was nonetheless able to to inherit a sum of more than £2,000 and return to England. For some reason Lisle waited until May of 1928 to return to England. Boarding the Passenger Ship ‘City of Poona’ at Cape Town, and taking a first class cabin, she and her 7 year old son returned to England – to Priestly Road, Wimbourne. Returning to England after what must have been a comfortable and colonial lifestyle in South Africa cannot have been easy. Perhaps for this reason Lisle decided to return to South Africa with Billy (by then 8 years old) and took a first class cabin on board the City of Nagpur, leaving from London on 19th January 1928. The ship’s papers show their intended permanent residence as Cape Town. Oral history relates that Lisle and Billy took a bungalow somewhere in Cape Town, intending to live there permanently. Unfortunately their plans were disrupted when Billy contracted Collitis sometime in late 1929. Billy was brought home to England by his mother in December 1929 where, despite their earlier plans, they remained. Their days in South Africa were over. Living at 9 Priestly Road with Lisle’s parents, Billy grew up in Kinson. Attending a fee-paying grammar school in Parkstone, he would have received a good education. Upon leaving school he became a car mechanic. His interests were not only mechanical but also lay in flying. Lisle paid for him to join the Bournemouth Flying Club, where he obtained his Aviator’s certificate on 20th March, 1939. No doubt observing events in Europe, Billy was keen to fly and join the RAF. Within 3 weeks of the start of the Second World War, WH Budd had joined up.

The Second World War Joining the RAF as an Aircraft Hand (Volunteer Reserve) at RAF Uxbridge on 20 September 1939, Billy immediately set about becoming a pilot. Following postings to Hastings and Cornwall he was posted to No 11 Elementary Flying School in Perth, Scotland on 19 August 1940 in the rank of Sergeant. Following flying courses at Ansty in Wiltshire and Tern Hill in Shropshire he was designated a Pilot in early November 1940 and awarded his Flying Badge with 89 hours solo in the Avro Anson entered in his log book. Commissioned on 10 December 1940, Pilot Officer Budd attended the No 13 School of Navigation (Pilots) Course but unfortunately failed the navigator’s course. Following operational conversion to Handley Page Hampdens in Upper Heyford, he was ready for this first operational posting. Pilot Officer Budd was posted to his operational unit, No 44 Squadron, at RAF Waddington in North Lincolnshire on 19 April 1941. 44 Squadron shared the base with No 50 Squadron, both part of No 5 Group, Bomber Command. The squadron, first formed in 1917, was by then equipped with the Handley Page Hampden bomber (as was all of No 5 Group at that time). Delivered to the RAF in 1938, this 4 seat bomber had a range of 1,200 miles carrying 4,000lbs of bombs, and 1,800 miles with a lighter 2,000lb bomb load. With a crew of 4 (pilot, navigator/bombardier/gunner, radio operator/gunner and rear gunner), the Hampden was characterized by a slender fuselage which meant that crew could not easily change places (nor wounded crew be removed from their seats) during flight. This slender shape and also prevented the installation of rotating gun turrets and meant self defence was weak - the aircraft was quickly moved to night bombing in 1940 following heavy daylight losses. In common with may new pilots, Billy spent his first five months flying as a navigator for more experienced pilots as he became familiar with the aircraft and operational duty. Flying firstly with Flying Officer Robertson and then Pilot Office Anekstein, Billy flew fourteen missions between April and the end of August 1941. These missions encompassed the bombing of strategic targets in Northern Germany (Husum Aerodrome, Cologne, Hamm railyway depot, Hanover), attacking the Battleships Sharnhorst and Gneisnau, at that time in dry dock under repair, and undertaking ‘Gardening’. These latter missions deployed the Hampden in one of its best-suited roles – mine laying. Carrying underwater mines dropped by parachute, Billy dropped ‘Vegetables’ (code for mines) in codenamed sea areas Eglantine (Helgoland); Nectarine (Frisian Islands), and Jellyfish (Brest).

Whatever the mission, operational sorties were arduous and frightening, lasting up to seven hours in freezing darkness. Due to the flying configuration of the Hampden, crew would no doubt feel very isolated. Flying through dense flak and searchlight batteries was commonplace, as was the loss of aircraft on many missions (in August and September 1941 44 Squadron lost 6 aircraft and crew in each of these months). Sorties were often cancelled due to bad weather (Billy never flew more than four times in any month) and so one can imagine a life dominated by routine and boredom, punctuated by short periods of intense excitement and fear. Loss of friends was all too common – the contrast between the hours on operational missions and daily life in the Lincolnshire countryside must have been very hard to reconcile. No doubt all too keen to take the controls, Billy flew his first operational mission on 31st August 1941, three weeks before his 21st birthday. Flying AE 257X, this was to be the aircraft he flew for the rest of his time on the Squadron. His crew were to become the regular crew for these sorties, comprising Sergeants Schafheitlin (navigator, from Canada), Austin (radio operator) and Hughes (rear gunner). His first two missions were ‘gardening’, followed by missions in September bombing the docks at Boulogne (on his 21st Birthday) and the cities of Hamburg and Frankfurt. During September the Squadron was given the title ‘Rhodesia’ Squadron, recognising the large number of Rhodesian aviators who were then on the squadron strength. One such individual was Sergeant Moore whose account of Billy’s mission on 15th September to Hamburg neatly pierces the typically anodyne mission reports which are found in the Squadron’s Operations Record Book and vividly describes what sorties were really like. He writes: “…and so I duly arrived at Waddington. I was on ops that very night with Budd, target Hamburg, having never previously flown Hampden! Naturally all sorts of trouble not the least of which was that I was desperately cold and had the greatest difficulty getting the best out of the hot air pipe. At that time it was becoming apparent that they were using a blue coloured master searchlight which was probably radar directed. Over the target one caught us and we were quickly coned. Our prompt evasive action with a full bomb load on board ended up in a spin and we came haring down. It went on and on and we thought about baling out, but with the swing of the spin and the ‘g’ forces, I couldn’t get the escape hatch open. The ‘g’ forces that accompanied the subsequent pull out were something terrific. After that we pushed off at low level. All sorts of flak and everything else had a go at us, it was safer than being higher up. For my part I thought it was absolutely terrifying.”

Following sorties to bomb the Krups factory at Essen on 10th October, and the chemical factory at Huls on the 12th, Billy’s crew took off on 21st October at 6.35pm as part of a sortie totaling 153 aircraft, their target Bremen. The entry in the Squadron Operations Record Book is typically brief in detailing an all too frequent occurrence: P/O Budd failed to return from his operation. P/O Budd took off at 18.35 hours and thereafter nothing was heard from this aircraft and the whole crew, as under, were posted “missing”. HAMPDEN AE257 Pilot P/O W.H. Budd Observer. No. R.65153. Sgt. D. Schafheitlin WO/AG. No. 910543. T/Sgt. W.E. Austin Rear Gunner No. 929395. T/Sgt. M.J. Hughes Although the exact fate of AE257 is not known, it is believed that the aircraft was shot down over the North Sea. Billy was eventually buried at Sage War Cemetery 30 miles West of Bremen and Sgt Hughes is buried at Becklingen War Cemetery, some 70 miles East of Bremen. Sgt’s Schafheitlin and Austin are commemorated at the RAF memorial at Runnymede (near Windsor, England), where those without graves are remembered. The business of bringing in the dead from outlying cemeteries after the war was carried out by Grave Concentration Units. The ultimate resting place of soldiers and airmen is therefore not always a good guide as to where they died. With 2 identified bodies, and 2 more either unidentified (and in graves marked ‘unknown’) or never found, it remains the most likely scenario at Billy and his crew were indeed shot down over the North Sea. The Waddington Station Raid book records Billy’s flight and scores it through with a red pen, denoting another crew lost in action. Billy’s mother Lisle, by this time 48 years of age, never visited the grave, but as a child in the early 1970s I remember being taken to the Sage War Cemetery by my father (who was serving in Germany with the Army at the time) to take a photograph for her. The Doc’s mother, Harriet, survived both her son Hayward and her grandson Billy, dying in Powick lunatic asylum in August 1942 aged 79. She left no will, and the details of her family were by then unknown.

Epilogue - John Hennesey (Lisle's Grand-Nephew) remembers ...

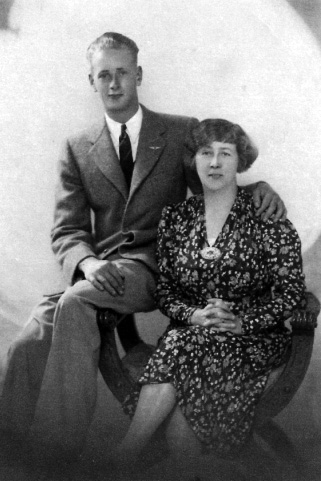

Billy and his mother Lisle, circa 1939. Anyone born at the turn of the 20th century was likely to live in remarkable times and Lisle was no exception. Having seen 2 World Wars, lived in South Africa, lost a husband and her only son, she lived out her days at 9 Priestly Road with her sisters Maud and Kate. I still remember visiting Priestly road as a young boy and spent a summer there once. I explored the old workshop at the end of the garden, and found some of Billy’s tools and his aviation magazines. I played in the garden where he had played cowboys and Indians many years earlier. Often Lisle would take me upstairs and sitting me on the edge of her bed, my legs dangling, take out Billy’s leather-bound logbook from her bedside table. She would show me the entries from his first flight he took in a Gypsy Moth before the war to the one before his last sortie in late October 1941. A picture of Billy was always above her chair in the front room. This card-backed photograph is now out of its frame, stained and almost ruined, but still exists. So does Billy’s silver cigarette case, engraved with his ranks of Sergeant and Pilot Officer, now in my possession. In accordance with her wishes, upon Lisle’s death in April 1989 (aged 96), her ashes were scattered over Kate’s grave. It is hard to concieve the events and changes Lisle witnessed at first hand – from the late 19th century when powered flight had yet to be attained, motor cars and electricity were in their infancy, to the late 20th century, which was a world of colour televisions, men landing on the moon and supersonic travel. She lived a long life, much of it without her husband and son, no doubt reliving so many memories. To the memory of Lisle, The Doc and Billy. John Hennessey [June 2009]

Do not stand at my grave and weep. I

am not there, I

do not

sleep.

References

Back to Main Page ...

|

|